How Gorsuch made the case for banning Trump from the ballot

Life comes at you fast.

This free edition of Public Notice is made possible by paid subscribers. If you aren’t one already, please consider taking advantage of our holiday special.

Bombshells don’t get much bigger than the Colorado Supreme Court ruling that Donald Trump is disqualified from appearing on the state’s presidential primary ballot because he engaged in insurrection. In doing so, Colorado came to the opposite conclusions of state courts in Minnesota and Michigan and is thus far the only state to take this step.

The Colorado court split 4-3 on the case, and the majority opinion can be thought of as two pieces. The first is based on the state’s election law and whether it allows Colorado voters to challenge Trump’s inclusion on the ballot. The second is an examination of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment’s language prohibiting someone who engaged in insurrection from holding office. That Amendment was passed shortly after the Civil War, and Section Three was specifically intended to bar federal officers and military officers who served in the Confederate government from being able to serve in federal office.

The plaintiffs in the Colorado case didn’t sue Trump. Rather, they sued the Colorado Secretary of State, Jena Griswold. Colorado’s election laws allow a voter to sue someone charged with an election duty who has committed or is about to commit a wrongful act. Here, the plaintiffs argued that Griswold would be committing a “wrongful act” by placing Trump’s name on the state’s presidential primary ballot because the state’s election code limits ballot access to “qualified candidates” only.

The surprisingly strong constitutional case for Trump's disqualification

The 14th Amendment is quite clear that insurrectionists can't hold office.

last. And the case for disqualifying Trump is stronger than you might think.

The Colorado Republican State Central Committee (CRSCC) intervened in the lawsuit, arguing that any determination about Trump’s qualifications to be on the ballot interfered with the party’s First Amendment right of association to choose its candidates. However, putting aside the whole insurrection issue, the United States Constitution sets out several conditions that have to be met for a person to be qualified to run for president. You must be a “natural born citizen,” at least 35, and have lived in the United States for at least 14 years. The CRSCC’s position, the Colorado Supreme Court pointed out, would allow them to place anyone on the ballot even if they didn’t meet these constitutional qualifications.

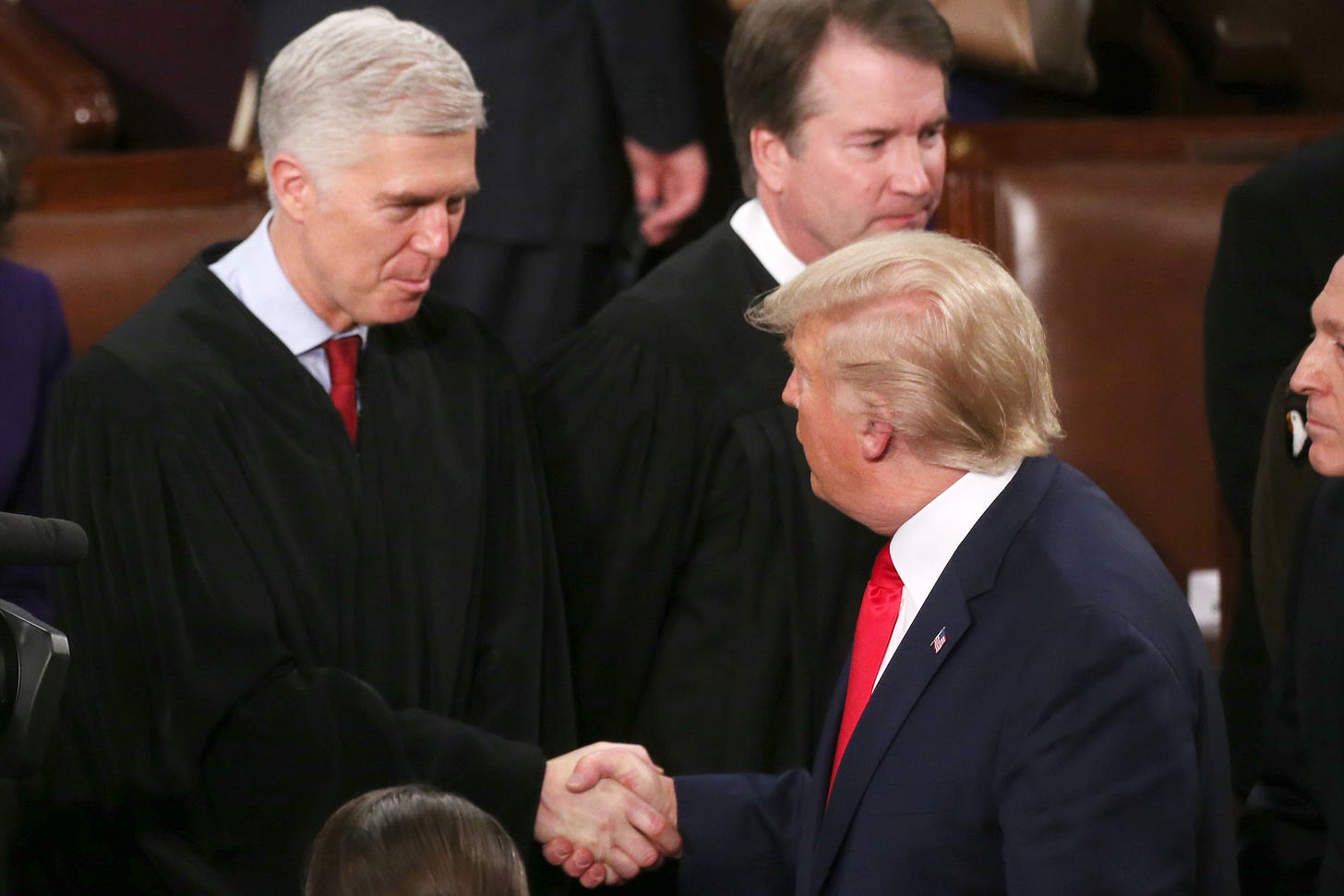

Trump also tried to argue that he is not barred from running for office because he’s an insurrectionist but only from holding office as an insurrectionist. This is absurd on its face, and the Colorado Supreme Court was able to dispose of that argument thanks to Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Really.

Back in 2012, Gorsuch was a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. In that capacity, he wrote the panel opinion in Hassan v. Colorado. Hassan, a naturalized citizen, sued Colorado, arguing it was required to put him on the presidential ballot even though he was not a natural-born citizen and was therefore not constitutionally qualified to run for president. The Tenth Circuit ruled against him, with Gorsuch writing that states have “a legitimate interest in protecting the integrity and practical functioning of the political process” and that because of that, they can “exclude from the ballot candidates who are constitutionally prohibited from assuming office.” It’s that quote that makes its way into the Colorado Supreme Court opinion.

Trump also complained that litigating his qualifications under Colorado’s “wrongful act” election provision wasn’t fair because it’s an expedited process — election challenges have to be heard quickly because of the tight deadlines for elections. Trump wanted to file additional motions, have extended discovery and disclosure times, depose expert witnesses, and so on. These are all ways in which Trump has been able to gum up the works in his federal cases, allowing him to drag them out, he hopes, past the 2024 election. But the Colorado Supreme Court pointed out that Trump has never explained what, precisely, he needed in terms of additional discovery or what other evidence he would have provided, undermining his own claim that he needed more time.

Originalism comes back to bite Trump

After the Colorado Supreme Court determined it was proper to sue under the state’s election law to keep Trump off the ballot, it still had to address the specifics of whether Trump engaged in insurrection.

Trump’s arguments against this, and the arguments of intervenors on his behalf, were comically numerous. To unpack them all first requires looking at the whole of Section Three:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

First, Trump argued that Congress never authorized the states to bar someone from office under Section Three’s prohibition on insurrectionists. He also contended that the issue of his qualifications was a “nonjusticiable political question” — essentially a separation of powers argument that only Congress could decide. He argued the presidency is not an “office, civil or military, under the United States.” He said the president is not an “officer of the United States.” The intervenors argued that since the oath taken by the president doesn’t require him to pledge to “support” the constitution, he can’t be disqualified from future office based on it. Trump said his conduct didn’t meet the definition of insurrection, that even if there was an insurrection, he didn’t “engage in” it.

To address these arguments, the Colorado Supreme Court did a very careful originalist analysis. Originalism is a favorite legal doctrine for conservatives, based on the idea that a constitutional provision has to be interpreted as it would have been at the time of adoption. It’s the logic behind Justice Samuel Alito’s opinion when the Court overturned abortion rights in Dobbs v. Jackson, with Alito traipsing through state statutes from the 1800s to hold that since abortion wasn’t protected then, it certainly can’t be now. And it’s the logic behind Justice Clarence Thomas’s opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, where the conservative majority declared that gun laws are constitutional only if there was a “history and tradition” of similar ones at the time of the nation’s founding.

A note from Aaron: Working with brilliant contributors like Lisa requires resources. To support this work, please click the button below and become a paid subscriber.

The Colorado Supreme Court made sure to follow this originalist path, focusing tightly on what was happening when the Fourteenth Amendment was being debated and ratified in the aftermath of the Civil War. It dug into how dictionaries from the time of the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment defined words like “office.” It looked up the draft versions of the Fourteenth Amendment. It quoted congressional speeches from 1866, pointing out that when Section Three was adopted, citizens understood that it disqualified oath-breaking insurrectionists from being president. It reviewed a compilation of messages and papers from the presidents stretching from 1789-1897 to learn that many 19th century presidents referred to the presidential oath as one to “support” the Constitution.

The Colorado court ultimately said Trump’s position asked them to come to an absurd conclusion: “to hold that Section Three disqualifies every oath-breaking insurrectionist except the most powerful one and that it bars oath-breakers from virtually every office, both state and federal, except the highest one in the land.”

SCOTUS is making major decisions based on outright lies

A case aiming to get rid of a wealth tax is just the latest example of justices indulging right-wing make believe.

Put that way, it sounds like a slam dunk, but the biggest hurdle for the plaintiffs here was that Congress never passed laws to authorize state courts to enforce Section Three. The Colorado Supreme Court majority opinion looked at cases decided shortly after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to hold that, along with the other Reconstruction Amendments passed right after the Civil War, this section was “self-executing.” In this context, “self-executing” means the constitutional provision is enforceable even though Congress passed no legislation to implement it. The plaintiffs argued, and the court agreed, that to find the Reconstruction Amendments were not self-executing would lead to unreasonable results because Congress could simply have nullified major civil rights amendments by refusing to pass any implementing legislation.

Between this historical analysis and the extensive quoting from Gorsuch’s opinion in Hassan, it’s clear that the Colorado majority opinion is carefully drafted to influence just six people in the country — the conservatives on the United States Supreme Court. It seems depressingly inevitable that the conservative majority will not let this decision stand. Still, Colorado will at least have made it really awkward for them by coopting their originalist approach.

It’s about time someone stood up for the Constitution

Since the Colorado decision ultimately turned on that state’s election laws, this ruling doesn’t necessarily provide guidance for cases brought in other states. Because each state sets its own election laws, Colorado could come down on the other side of Minnesota and Michigan. For example, the Colorado Supreme Court explained that unlike Colorado, Michigan’s election laws don’t contain the term “qualified candidate” and don’t enable Michigan state courts to assess the qualifications of a presidential primary candidate. However, the Colorado court’s careful historical analysis of the origins of Section Three can certainly be used by plaintiffs or courts in other states, as that analysis revolves around the passage of a federal constitutional amendment.

There’s plenty of speculation as to how this will simply empower red states to throw Democrats off the ballot by stretching the definition of “insurrection” to mean “anything a Democrat does that Republicans don’t like.” But that speculation overlooks that Republicans have already gone to great lengths to undermine the integrity of elections and to make sure Democrats don’t win. Conservative courts have radically diminished the scope of the Voting Rights Act, red state legislatures have passed gerrymandered maps that help ensure GOP victories, and Trump fans have terrorized state election officials.

Yes, Colorado’s ruling may give the GOP additional reason to make a mockery of elections, but they were going to do that regardless. At some point, Democrats owe it to themselves — and to the country — to uphold the Constitution even as the GOP tries to tear it down.

That’s it for today

We’ll be back with more tomorrow. If you enjoy this post, please support Public Notice by signing up. Paid subscribers make this work possible.

Wonderful piece on Colorado S Ct!

It’s interesting that R’s always trumpet states’ rights and originalism/textualism when it suits them. But not now. This proves the Federalist Society types are about naked power politics and NOT the Constitution; not a surprise. Just proves R’s want to rule, not govern.

If dreams come true, and the rest of the PutinRepublicans are voted into the downward flushing vortex with TFG, major legislative steps must be made to fortify our democracy.