SCOTUS plays dumb as Trump claims sweeping immunity

Civil? Criminal? Who can tell the difference? Not Supreme Court justices!

PN is a reader-supported publication made possible by paid subscribers. If you aren’t one, please click the button to support our independent journalism.

Last week, the Supreme Court heard arguments on whether a sitting president is above the law. The answer was a resounding “no … probably.”

This would not, at first blush, appear to be a difficult question. After all, it’s axiomatic in America that no one is above the law. And yet the five male justices seem strongly inclined to find an exception to that rule, particularly Justice Samuel Alito, who wondered whether it might not be better to let presidents do crimes lest they be encouraged to stage a coup to avoid the possibility of being “criminally prosecuted by a bitter political opponent.”

“Will that not lead us into a cycle that destabilizes the functioning of our country as a democracy?” he sniffed, as if we weren’t talking about holding to account a defendant who actually tried to mount a coup — the very thing Alito claims would be prevented if we just let presidential bygones be bygones.

But the sheer outrageousness of Alito’s suggestion may have overshadowed the radical position of his fellow conservatives, all of whom seemed to think the question of whether the president has to obey the laws of this land is a major head scratcher. Only Justice Amy Coney Barrett seemed to work from the premise that the president doesn’t get a pass for actual crimes, but even she seemed amenable to imposing a balancing test that will add months if not years before the case against Trump could actually go to trial.

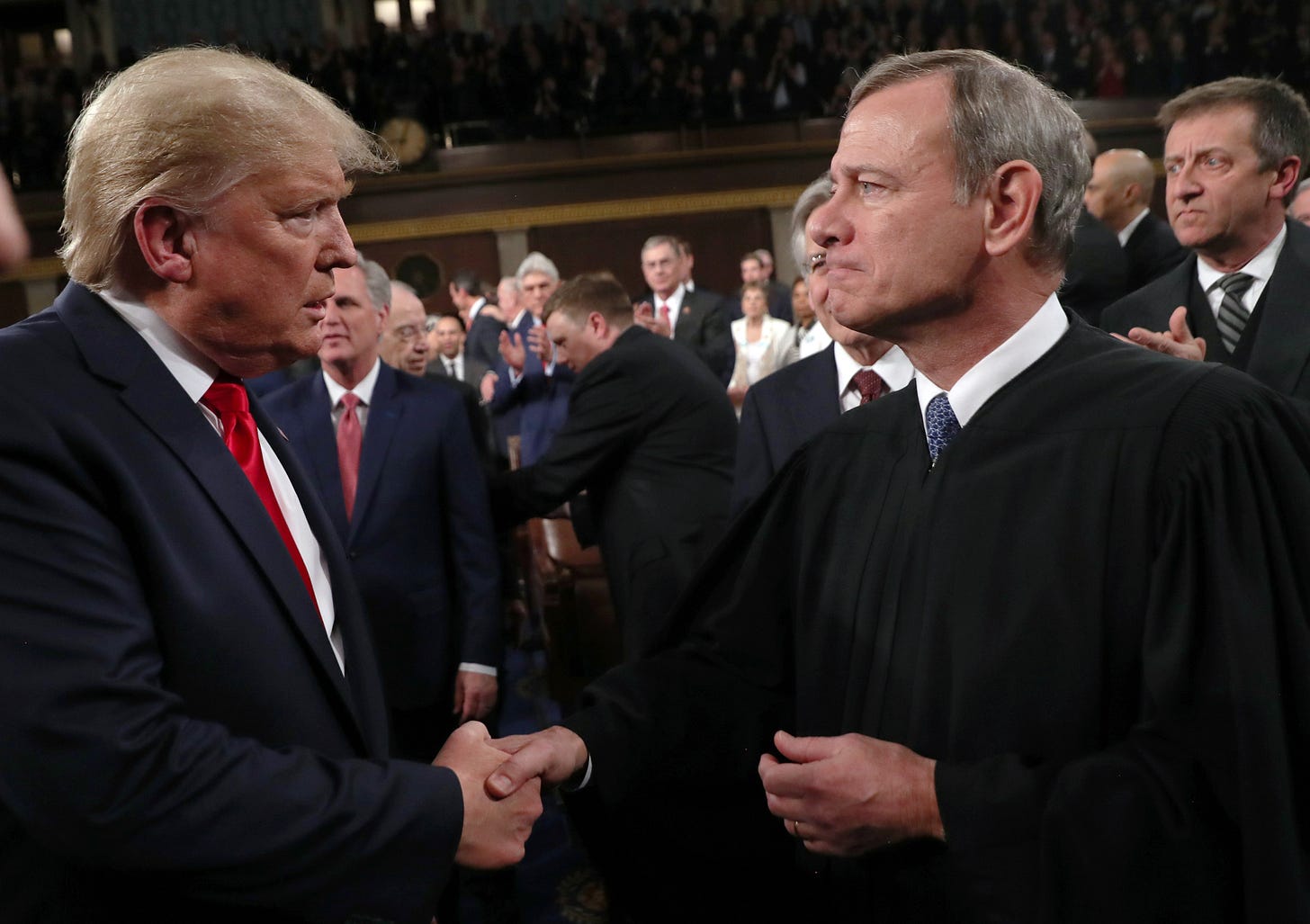

By contrast, Chief Justice Roberts — who began the hearing by noting that appointing ambassadors is part of the president’s official duties, but it’s still criminal bribery to sell appointments — seemed to want to toss Trump a lifeline. Roberts pulled one phrase from the Circuit Court’s ruling and called it “the clearest statement of the court's holding, which is why it concerns me.”

"‘A former president can be prosecuted for his official acts because the fact of the prosecution means that the former president has allegedly acted in defiance of the laws,’” the Chief Justice quoted derisively, adding that “it sounds tautologically true.”

The quote, appearing smack in the middle of the DC Circuit’s opinion, has to do with whether the federal judiciary has jurisdiction to hear the prosecution of the former president. It’s not the appellate court’s holding, and to pretend otherwise is a grossly disingenuous move intended to diminish an incredibly well-reasoned and thorough opinion.

Here’s what the three-judge panel below actually held:

We cannot accept former President Trump’s claim that a President has unbounded authority to commit crimes that would neutralize the most fundamental check on executive power — the recognition and implementation of election results. Nor can we sanction his apparent contention that the Executive has carte blanche to violate the rights of individual citizens to vote and to have their votes count.

At bottom, former President Trump’s stance would collapse our system of separated powers by placing the President beyond the reach of all three Branches. Presidential immunity against federal indictment would mean that, as to the President, the Congress could not legislate, the Executive could not prosecute and the Judiciary could not review. We cannot accept that the office of the Presidency places its former occupants above the law for all time thereafter.

Which is a lot harder to grapple with, and so the high court’s conservatives simply chose not to. Instead they played along with Trump’s lawyer, John Sauer, who argued that the Court’s civil immunity rulings with respect to Richard Nixon necessitated finding criminal immunity for Donald Trump.

The Nixon precedents

To be clear: the Supreme Court has never held that presidents are immune from criminal prosecution.

In US v. Nixon and later in Trump v. Vance, SCOTUS held that presidents are not immune from having to comply with criminal investigations and subpoenas — which would certainly seem to imply that they could later be prosecuted. The Court forced Nixon to turn over his White House tapes, after which he immediately resigned. Gerald Ford then pardoned Nixon (and he accepted!) because everyone understood that Nixon was about to be indicted for crimes he’d committed while in office.

Nevertheless, Trump argues that a later case called Nixon v. Fitzgerald implies that he enjoys absolute criminal immunity for any “official acts” taken while he was president.

A note from Aaron: Working with brilliant contributors like Liz requires resources. If you aren’t a paid subscriber, please click the button below to support our work.

In Fitzgerald, an Air Force contractor sued the president alleging that he’d been fired in an act of unlawful retaliation after he testified before Congress. The Supreme Court rejected Fitzgerald’s claim against Nixon personally, finding that the president enjoys absolute civil immunity for official acts. They reasoned that anyone on earth can march into federal court and file a civil suit, and it would be unfair to subject the president to potentially millions of lawsuits as a result of holding office. Fitzgerald was then narrowed by the Supreme Court in 1997’s Clinton v. Jones, in which the Court held that civil immunity only protected the president for official acts, and not personal ones.

Perhaps wary of grounding their holding on the second most reviled president in modern history, the Court’s conservatives sought to tie this case to a more recent suit filed by Officers James Blassingame and Sidney Hemby, who were at the Capitol when Trump’s followers attacked it.

In March 2021, the officers sued the former president for inciting the riot and directing, aiding, and abetting assault and battery. Trump moved to dismiss on grounds of absolute civil immunity, but was rebuffed by Judge Amit Mehta at the trial court. Trump appealed, arguing that all presidential speeches on matters of public concern were by definition official acts, and thus entitled to immunity under Fitzgerald and Jones. But in February 2024, the DC Circuit upheld the trial court’s ruling, writing:

While Presidents are often exercising official responsibilities when they speak on matters of public concern, that is not always the case. When a sitting President running for re-election speaks in a campaign ad or in accepting his political party’s nomination at the party convention, he typically speaks on matters of public concern. Yet he does so in an unofficial, private capacity as office-seeker, not an official capacity as office-holder. And actions taken in an unofficial capacity cannot qualify for official-act immunity.

Like Fitzgerald, Blassingame is a civil case. But the Republican appointees seized on its official versus personal distinction as an excellent framework to apply to the criminal case before it.

Justice Kavanaugh opined that “the president's not above the law. The president's not a king,” as if to assure the listeners that he’s not a loon like Alito, before adding that “I think your point in response to that is the president is subject to prosecution for all personal acts, just like every other American for personal acts. The question is acts taken in an official capacity.”

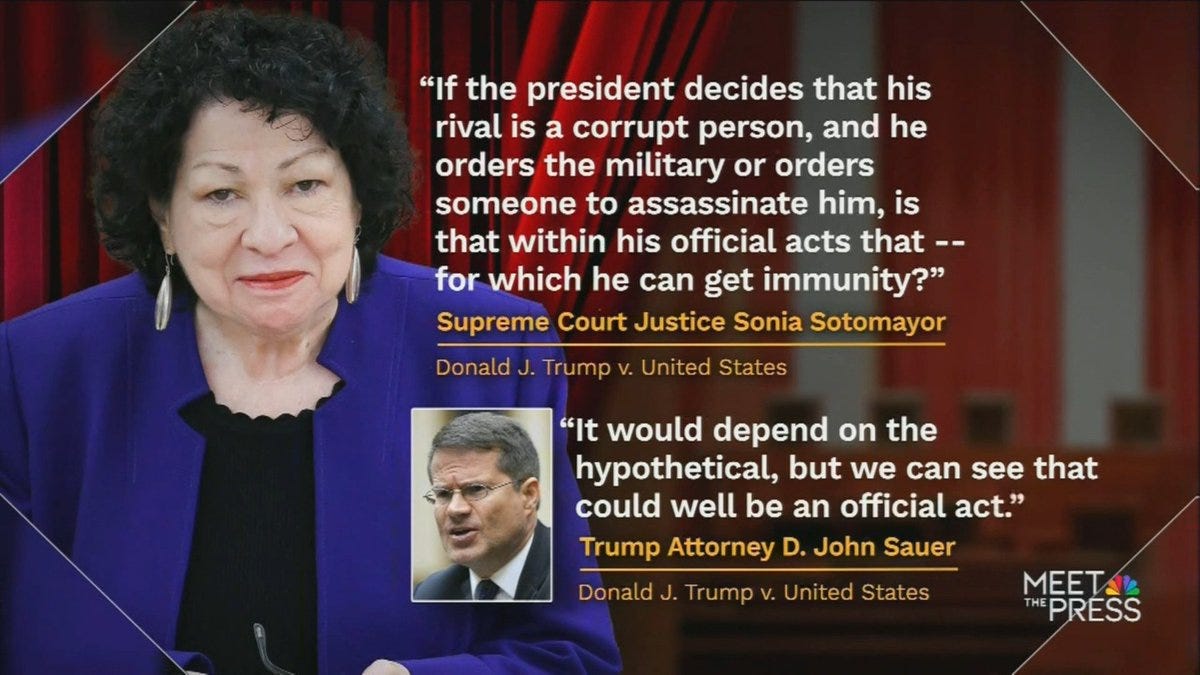

The premise of this question is that there is some kind of immunity for presidential acts taken in an official capacity, even those that are blatantly criminal. As Judge Florence Pan pointed out when this case was argued at the DC Circuit, that would mean that a sitting president could not be prosecuted for ordering SEAL Team 6 to assassinate his political rival — something which simply cannot be the case. And so Kavanaugh and Gorsuch simply plowed across the rhetorical median strip to merge the criminal case against Trump with the civil one, blithely disregarding all the Nixon precedents to reach his preferred outcome.

“The D.C. Circuit in Blassingame, chief judge there joined by the panel expressed some views about how to segregate private conduct for which no man is above the law from official acts,” Justice Gorsuch asked. “Do you have any thoughts about the test that they came up with there?”

“Yes,” Sauer responded gamely. “It would be a great source for this Court to rely on in drawing this line. And it emphasizes the breadth of that test. It talks about how actions that are, you know, plausibly connected to the president's official duties are official acts. And it also emphasizes that if it's a close case or it appears there's considerations on the other side, that also should be treated as immune.”

After which, the conservative members of the court spent the rest of the morning batting around ways to retrofit the civil standard from Blassingame and Fitzgerald to the criminal prosecution of a former president.

“I'm not concerned about this case so much as future ones,” Gorsuch said, waving off Trump’s actual conduct.

“This case has huge implications for the presidency, for the future of the presidency, for the future of the country, in my view,” Kavanaugh agreed.

An utterly craven exercise

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson called out the conservatives in real time for tacitly expanding the Fitzgerald holding to cover criminal acts.

“Fitzgerald was a civil situation in which the president actually was in a different position than other people because of the nature of his job, the high-profile nature and the fact that he touches so many different things,” she said. “When you're talking about private civil liability … we could see that the president was sort of different than the ordinary person when you say should he be immune from civil liability from anybody who wants to sue him. But, when we're talking about criminal liability, I don't understand how the president stands in any different position with respect to the need to follow the law as he is doing his job than anyone else.”

This gets at the vital difference between federal civil lawsuits and criminal prosecutions. Criminal charges require federal prosecutors to investigate, grand juries to indict, federal judges to sign off on warrants, even more federal judges to oversee pretrial proceedings, jurors to convict, and appellate judges to review, and finally the Supreme Court itself, standing as a check over all of them, to see that nothing goes wrong. In short, the system has multiple layers of protection from unlawful criminal prosecution which simply do not exist in civil cases. That’s why it took a special counsel upwards of three years to get here today!

In response, Alito trotted out the old saw about prosecutors being able to “indict a ham sandwich.”

“The vast majority of attorneys general and Justice Department attorneys are honorable people and they take their professional ethical responsibilities seriously. But there have been exceptions, right?” added the man who spent every single second of his professional life since graduating from law school as an employee of either the federal judiciary or the Justice Department.

Even for Alito, it’s remarkably craven to wave away the entire judicial edifice — particularly when he, himself, sits atop of it! — as so inherently corrupt that presidents should be insulated from responsibility for crimes, lest they be persecuted by their successors.

And yet that’s precisely what most legal observers now expect the Court’s conservatives to do: adopt some version of the official/unofficial acts test, implicitly recognizing the president’s immunity for crimes committed in office as long as he can claim some nexus with his official duties. Then they can send Trump’s criminal case back to the trial court for a fact-intensive and time-consuming inquiry as to whether he was acting in his official capacity when he tried to persuade Mike Pence to reject the real electors and substitute fake ones, and then dispatched his followers to disrupt certification of President Biden’s victory.

The reality is that, if this case is allowed to proceed to trial — that is, if Trump loses and and hence can’t blow it up from the Oval Office — then the Supreme Court will probably have bought him nothing but time. Sauer himself conceded that much of the conduct alleged in the complaint is purely personal. Trump will argue that he had a right to “lobby” Congress and Pence, but that would certainly appear to be in his capacity as a candidate, not an incumbent.

But the costs for the country, particularly if Trump gets a second term, will be disastrous.

That’s it for today

We’ll be back with more tomorrow. If you enjoy this post, please support Public Notice by signing up. Paid subscribers make this work possible.

Thanks for reading.

So if Prez Immunity is a thing, and if Trump "wins," (!) then Biden would be acting in his official capacity to persuade Kamala Harris to reject the real electors and substitute fake ones, and then dispatch his followers to disrupt certification of Trump's victory??

OKAAAY then.

Given the calendar, this will be remanded; causing no decision and thus no trial before the election. So, in essence TFG will get what he needs. Kudos to Sen Whitehouse for shining a light on the court.