The Supreme Court's "deal with the devil"

A recent decision gutting the Clean Water Act shows how business interests trump principle for the court's right-wing majority.

Public Notice is supported by readers and funded by paid subscribers. To help make this work sustainable, please consider becoming one.

By David R. Lurie

Today’s radical right-wing Supreme Court majority is the product of a “deal with the devil,” struck between evangelical Christians focused on voiding Roe v. Wade and billionaires’ obsession with government efforts to regulate their businesses, especially their incessant pollution of the nation’s air and water. Both sides are getting what they wanted, at the expense of the American people.

Much attention has been focused on the Supreme Court’s relentless attacks on civil rights, reproductive autonomy, and the establishment clause’s separation of church and state. But there is another equally important element to the reactionary counterrevolution the justices and their sponsors are engineering: an attempt to void the federal government’s authority to enforce the nations’ workers’ rights, financial regulation and, particularly, environmental protection laws.

RELATED FROM PN: A brief history of the right-wing scheme to corrupt the Supreme Court

The Kochs and Crows did not spend millions upon millions of dollars to remake the courts solely because of their affinity with conservative religious doctrine; they did it because the investment was good for business. It is hardly a coincidence that many of the hyper-wealthy plutocrats who have funded the court-packing project are in businesses like real estate development and chemicals — industries with a long history of violating environmental law and challenging the authority of the EPA and other federal agencies.

During recent years, the Rev. Robert Schenck, a longtime anti-choice activist who was part of a carefully organized evangelical Supreme Court influence operation, became a whistleblower, and acknowledged the highly transactional deal that right-wing Christians struck decades ago with business owners.

As Schenck recounts, Republican operatives could not have been blunter regarding the deal they wanted, stating during one consequential meeting with evangelical leaders: “You guys want Roe v. Wade overturned, we can do that for you. But you take the whole enchilada, you take the whole thing.” As Schenck ruefully admits: “From that point on that community that I had served, and still do, made a deal with the devil,” obligated to “support everything on the conservative agenda, whether or not we had conscientious conflict with them. The means were justified by the ends of that.” (You can watch some of Schenk’s December 2022 congressional testimony below.)

In order to realize their goals of re-criminalizing abortion and melding church and state, conservative Christians agreed to lend their support to populating the courts with judges who also favored the radical, anti-”regulatory state” agenda of the billionaires who were funding the campaign. The deal was struck.

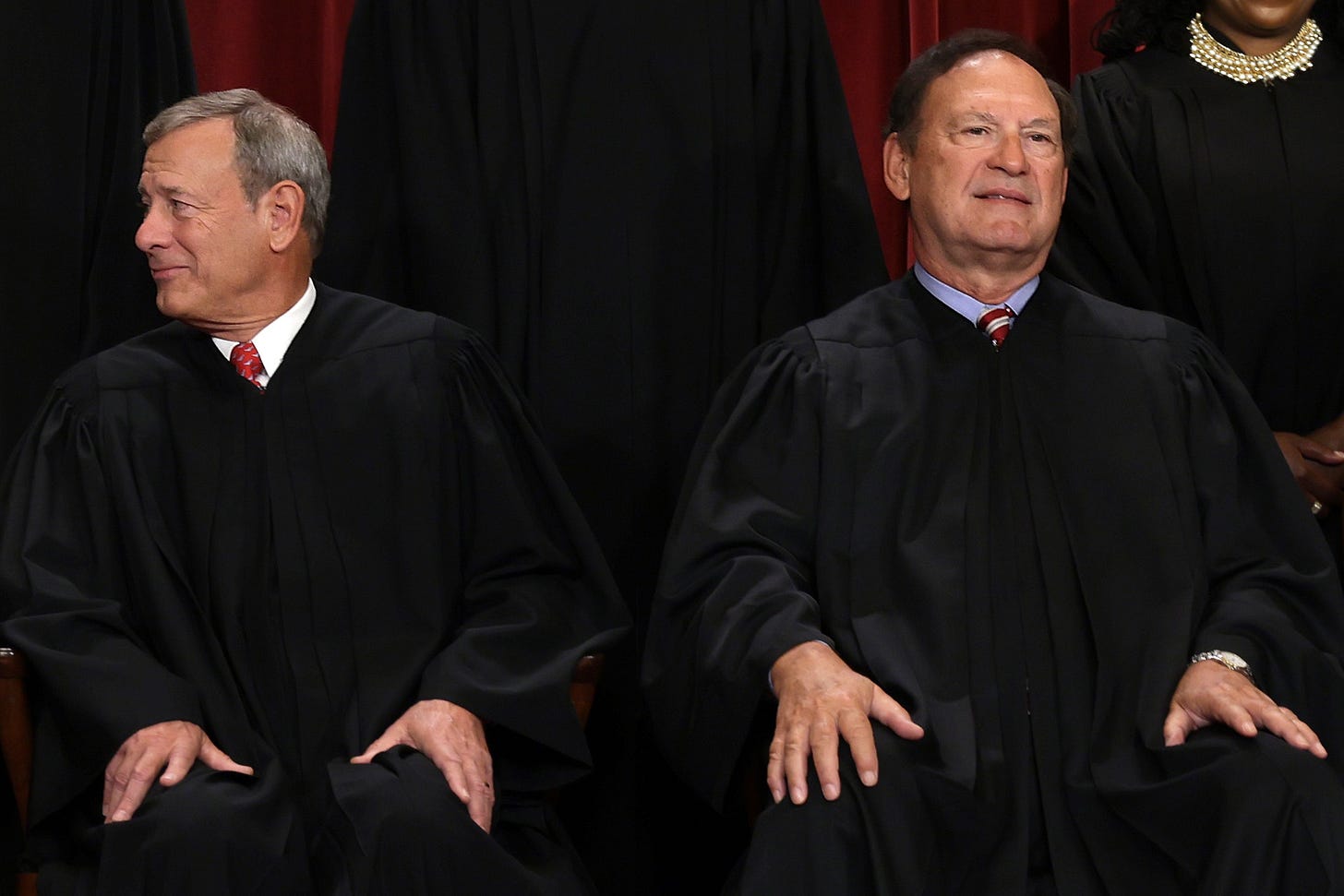

The result has been a judiciary, and particularly a Supreme Court, dominated by judges like Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, who are as passionate about increasing pollution and voiding workers’ rights as they are about taking away women’s rights to control their own bodies.

The Supreme Court’s attacks on the foundations of environmental and other critical regulatory regimes, however, often appear very technical in nature, and rarely get the kind of public and press attention provided to abortion and civil rights decisions. This lack of attention only makes it easier for the court’s right-wing justices to serve the interests of their sponsors, often in the most shamelessly obvious of ways.

Alito and company’s commitment to “textualism” doesn’t extend very far

A case in point was last month’s decision in Sackett v. EPA, in which five right-wing justices blithely discarded their own purported judicial principles in the cause of freeing developers and industrialists to pollute the nation’s water free from pesky regulatory interference.

At issue in Sackett was the scope of the 1972 Clean Water Act, a landmark piece of legislation responsible for preventing the nation’s waterways from turning into dumping grounds for all manner of poisons and other waste, as they had for most of the 20th century. The act gave the EPA authority to regulate “navigable waters;” a term that is broadly defined to include all “waters of the United States.”

Furthermore, the act was amended by Congress to expressly include wetlands “adjacent” to navigable bodies of water, and for good reason, since the protection of wetlands — which contain waters that ultimately feed into the nation’s river, lakes, and ocean waters — is not only important, but indeed essential, to addressing pollution as well as flood control.

For decades, consistent with the extremely broad statutory language, courts have agreed that the Clean Water Act’s scope extends beyond oceans, lakes, and rivers to include wetlands and intermittent streams that, ultimately, feed into such bodies of water — regardless of whether they are literally connected to such navigable waters — recognizing that reading wetlands out of the act would be contrary to the express language (as well as the purpose) of the law. Were the Supreme Court’s right-wing justices actually true to their purported “conservative” legal philosophy, they would not even have considered changing this longstanding interpretation of the Clean Water Act.

For years, right-wing critics accused purportedly “liberal” courts of “judicial activism,” which they defined as usurping the role of elected officials by disregarding the proper construction of the Constitution and duly enacted statutes, and effectively rewriting the nation’s laws to suit their own policy preferences.

RELATED FROM PN: The federal judiciary's grave legitimacy crisis

In supposed contrast, right-wing jurists claim to apply what they call “textualist” principles, by which judges purport to adhere to the “ordinary meaning” of statutory provisions, giving it effect regardless of whether doing so yields a result consistent with the politics of, or policies favored, by the judges handing down the decisions.

But in Sackett, five of the Supreme Court’s six right-wing justices were perfectly willing to give up their purported textualist principles, and thereby managed to reach a result long favored by industrialists, miners, and developers across the nation.

A note from Aaron: Working with brilliant contributors like David requires resources. To support this work, please click the button below and sign up to get our coverage of politics and media directly in your inbox three times a week.

In an opinion, predictably, authored by Alito, the majority excised vast swaths of wetlands and streams from the scope of the Clean Water Act, and did so by disregarding its broad statutory language — which plainly includes wetlands that feed into, and therefore are “adjacent” to rivers and lakes — and imposing in its place an entirely judicially created standard limiting the scope of the Act to streams and wetlands that literally “adjoin” such bodies of navigable water. Thus, the majority ruled, in order to fall within the scope of the act, a wetland must have “a continuous surface connection to” a river, ocean or the like, such that there is “no clear demarcation” between the two.

In support of his rewriting of the law, Alito offered arguments frequently heard from real estate investors, who have long complained about the scope of environmental regulations. Thus, Alito complained that the Clean Water Act has impacted “a staggering array of landowners” and impacted “mundane” activities like moving soil.

But as Justice Kagan argued in dissent, those are policy objections to the judgement of Congress in enacting the Act and the EPA in enforcing it, which is just what conservatives previously asserted that judges should never employ in reaching their decisions:

The majority shelves the usual rules of interpretation — reading the text, determining what the words used there mean, and applying that ordinary understanding even if it conflicts with judges’ policy preferences.

As Kagan went on to explain: “Because the Act covers ‘the waters of the United States,’ and those waters ‘includ[e]’ all wetlands ‘adjacent’ to other covered waters, the Act extends to those ‘adjacent’ wetlands,” not just wetlands that literally touch other bodies of water.” Furthermore, by writing large swaths wetlands that are close to bodies of water — which serve the critical role of filtering and purifying the waters draining into the nation’s lakes and rivers — out of the scope of the Clean Water Act, the majority frustrated the plainly stated purpose of the Act.

Alito’s rationale for rewriting the Act was not only weak, but dangerous. He invented a new rule: that Congress must employ “exceedingly” clear statutory language if it wants to alter the “balance between federal and state power and the power of the Government over private property.” Put otherwise, the court now considers itself free to change the rules of statutory interpretation to favor the interests of those who have long opposed environmental regulations.

The abandonment by the five justice majority of their long-stated adherence to conservative textualist principles was even too much for their ideological compatriot Justice Kavanaugh, who also dissented. But given the fact that the court now has a supermajority of right-wing justices, a dissent from one of its conservative members does not change the outcome.

The consequences of the Sackett decision are likely to be disastrous for the nation’s environment, and for the health of its citizens. Decades of hard-won efforts to clean up and preserve the safety of the nation’s water and waterways are being imperiled. But the shamelessness of Alito and his colleagues — and their willingness to brazenly discard the principles of judicial restraint and statutory interpretation they have long championed — signals an even greater danger.

The freedom to pollute

The court’s packed majority is determined to undermine the “regulatory state,” and with it environmental and other pesky laws that the billionaires who funded the packing of the nation’s courts have long desired.

Sackett is only one step in what is all but certain to be a series of rulings designed to systematically constrain the scope of federal environmental, as well as financial, labor, and workplace protection laws — as well as strictly limit the power of federal agencies to construe and enforce those laws.

For example, Sackett was preceded by last year’s 6-3 decision in West Virginia v. EPA, in which every member of the court’s right-wing majority agreed to to void a set of Obama-era EPA Clean Air Act regulations limiting greenhouse gas emissions by power plants, despite the fact that the Biden administration had expressly stated that it did not intend to enforce the rules.

Next term, the Supreme Court is going to consider voiding a longstanding doctrine requiring judicial deference to reasonable interpretations of ambiguous statutory terms, a step that would further increase its power to nullify environmental and other regulations.

In rare cases, two of the court’s right-wing justices can be convinced to step back from the brink and avoid taking it upon themselves to rewrite duly elected laws. Such was the case in Allen v. Milligan (decided this week), in which a bare majority of the court preserved a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, after two previous decisions which vandalized critical elements of that landmark civil rights law. But the trend toward right-wing judicial overreach is clear.

As Justice Kagan explained in her Sackett dissent, under our Constitution, it is up to the Congress, not the court, to “decide how much regulation is too much.” The court’s right-wing majority, however, is unwilling to accept the constitutionally assigned limitation upon their role. Instead they are increasingly brazenly taking it upon themselves to remake the law in accordance with their own ideology, and that of their sponsors.

The “deal with the devil” that right-wing Christian extremists and their billionaire sponsors struck decades ago is working out exactly as the dealmakers planned. But the American people were not parties to the deal, and are paying a huge price for it.