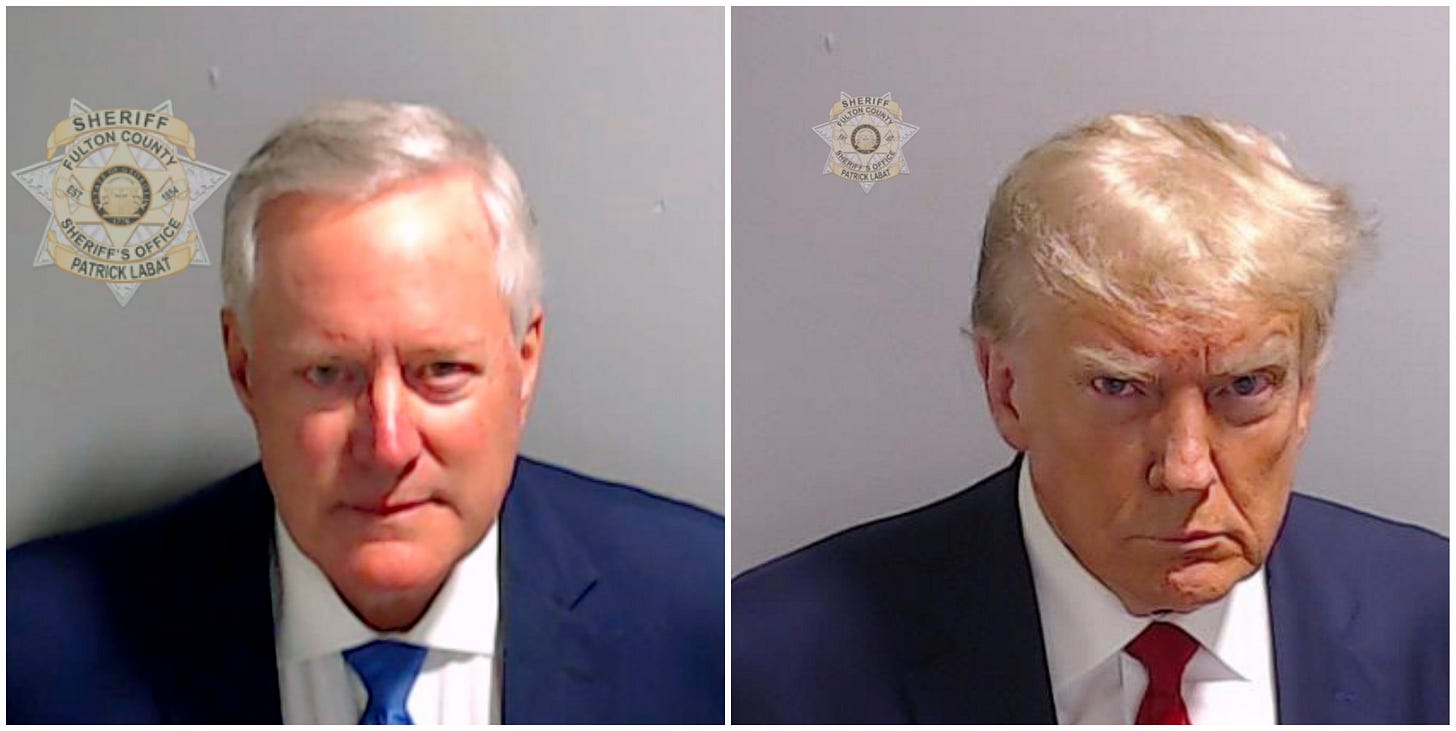

Mark Meadows lost big on Friday night. And so did Donald Trump.

Back to Fulton County for you!

🚨 WE’RE OFFERING FREE TRIALS FOR ALL NEW PUBLIC NOTICE SIGNUPS 🚨 Click the button to support this work and unlock full access to everything we publish.

On Friday night, a federal judge in Georgia sent the RICO charges against Mark Meadows back to state court. Within hours, the former White House chief of staff filed an appeal to the conservative 11th Circuit.

But even if Meadows eventually succeeds in getting the trial judge’s ruling overturned, Friday night’s order is very bad news, not just for Meadows, but also for his co-defendant and former boss Donald Trump.

Federal removal

On August 14, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis charged the former White House chief of staff with participating in a RICO conspiracy and soliciting a federal official to violate his oath of office. The bar for a federal official charged with a state crime to remove his case to federal court isn’t particularly high, and many commentators expected Meadows to clear it. After all, under 28 U.S.C. § 1442, Meadows just had to convince Judge Steve Jones (1) that he was a federal officer at the time the conduct occurred; (2) that the charged conduct was undertaken for or related to “color of his office”; and (3) that he could assert a colorable federal defense to the charges.

Obviously, there’s no dispute as to the first prong: Meadows was working at the White House during the presidential transition. As to the second, the issue is more complicated. Some of the “overt acts” referred to the indictment, such as scheduling meetings and retrieving phone numbers for the president, would appear to fall squarely within the chief of staff’s wheelhouse. Others, such as the infamous call where Trump pressured Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to “find 11,780 votes,” look like campaign activity.

A note from Aaron: Working with brilliant contributors like Liz requires resources. To support this work, please click the button below and take advantage of my special offer — free trials for all new signups.

In an August 28 hearing before Judge Jones, Meadows testified that his job was to handle anything which might occupy the president’s time and attention. It was part of his official duties to email Trump campaign official Jason Miller and say, “We just need to have someone coordinating the electors for the states,” Meadows insisted, shrugging off the use of “we” as a verbal tic leftover from his time in Congress. In his telling, a trip to Georgia to check in on the state’s signature audit and subsequent texts to officials wondering if an infusion of campaign cash might speed things along were part of his day job at the White House. Asked for an example of something — anything — which would exceed his official duties, Meadows speculated that giving a speech at a campaign rally might just do it. Meadows, who coordinated the pre-riot rally on January 6, even swore under oath that he was just trying to “land the plane,” assuring the president that the election had been conducted fairly so that they could all move on to planning for a peaceful transition of power.

Judge Jones was clearly unimpressed with this portion of Meadows’s testimony, writing that the witness “did not adequately convey the outer limits of his authority, and thus, the Court gives that testimony less weight.” And when a federal judge says he’s giving your testimony “less weight,” he’s saying you’re full of crap.

Being an official doesn’t make it “official business”

Willis countered Meadows’s expansive definition of his official role by pointing to the Hatch Act, which makes it illegal for executive branch officials to use their office to benefit a particular political candidate. Like Kellyanne Conway, who famously dismissed an alleged Hatch Act violating by scoffing “let me know when the jail sentence starts,” Meadows makes multiple appearances in a report by the Office of Special Counsel detailing the Trump administration’s routine disregard for the distinction between official and campaign activity. Willis attached this report as an exhibit, highlighting Meadows’s repeated use of his office for banned campaign activity, even as he boasted that “nobody outside of the Beltway really cares” about the Hatch Act.

But if Meadows was a little fuzzy on the scope of his employment, Willis has been criticized for drafting an overbroad indictment, loaded down with extraneous allegations. And after the hearing it looked like she might have made a serious error by including so many “overt acts” unnecessary to prove her case. Judge Jones ordered the parties to brief the court on what it should do if some, but not all of the conduct alleged was within the scope of Meadows’s official duties, raising the specter that Meadows would be able to get himself out of state court because prosecutors ran their mouths in the indictment. Commentators particularly focused on “Overt Act 6” in support of the conspiracy, in which Meadows “sent a text message to United States Representative Scott Perry from Pennsylvania and stated, ‘Can you send me the number for the speaker and the leader of PA Legislature[?] POTUS wants to chat with them.’”

In his ruling, Judge Jones agreed that “Overt Act 6” was likely part of Meadows’s job as chief of staff. But he reasoned that was ultimately irrelevant, since Meadows is charged with participating in a RICO conspiracy and soliciting a public officer to violate his oath, not getting a phone number or setting up a meeting.

“The Court determines that the actual ‘act’ alleged against Meadows is the RICO charge, not the overt acts,” he wrote, adding that the overt acts are part of a “broader story” outlining the conspiracy, but are “not the source of [criminal] liability.”

Citing the Hatch Act’s ban on executive branch employees doing campaign work on the job, the court ruled that Meadows was not acting as a government official when he participated in the alleged conspiracy.

“These prohibitions on executive branch employees (including the White House Chief of Staff) reinforce the Court’s conclusion that Meadows has not shown how his actions relate to the scope of his federal executive branch office,” Judge Jones wrote. “Federal officer removal is thereby inapposite.”

So, what now?

Meadows immediately appealed to the conservative 11th Circuit, and may yet get his wish to remove his case to federal court. But this ruling presents an immediate problem for his co-defendant Donald Trump. The former president has 30 days from his August 31 arraignment to seek removal of his own case to federal court, and he has indicated he plans to do.

If Meadows had succeeded in getting his case removed, Trump could have filed a motion saying, essentially, “Ditto.” Meadows was acting as Trump’s agent, and so arguably, if he was acting under color of his federal office for at least some of the alleged conduct, then so was Trump. Because the cases are related, Trump would have wound up in front of Judge Jones, where he could be reasonably confident of being able to use the Meadows ruling to piggyback his way into federal court.

But that’s not going to happen now. Even if the 11th Circuit expedites Meadows’s appeal and rules in his favor, it’s highly unlikely to do so before Trump’s September 30 deadline for removal. Trump will now have to file his own petition for removal before a judge who has already said that the controlling factor isn’t the overt acts, but the underlying crimes charged.

Meadows was so desperate to get into federal court that he testified at his hearing, likely waiving his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. And it didn’t even work!

Trump will never take the witness stand. First, because he’s an absolutely terrible witness, prone to both lying and impromptu outbursts, such as commenting on the sexual desirability of opposing counsel. Moreover, Trump has made repeated public statements attacking DA Willis in the most vulgar terms. There is no universe in which any lawyer will voluntarily put him on the witness stand at a removal hearing (or anywhere else), and particularly not when he might face cross examination by Willis herself.

But if testifying is out, it’s not clear how Trump is going to convince the court that he was doing official president stuff when he spewed debunked lies about election fraud, badgered swing state legislators and officials to steal Joe Biden’s electors, and, in the case of Secretary Raffensperger, urged him “find” votes and create a fraudulent electoral record. Who besides one of his co-defendants would testify in support of such a ridiculous proposition?

Even if Meadows (and Trump) win, they still lose

And even if Trump and Meadows manage to get themselves to federal court, they’re still going to have a problem with the third prong of the removal test, which requires them to assert a colorable federal defense, such as the First Amendment. In fact, before the court even considered his removal petition, Meadows filed a motion to dismiss the case under the Supremacy Clause, claiming immunity from state prosecution for conduct undertaken as part of his federal duties. But now Judge Jones has ruled that some, but not all of the conduct alleged was part of his job as chief of staff, implicitly rejecting the Supremacy Clause argument as to the crimes, if not the overt acts.

Similarly, Trump, Meadows, and other co-defendants seeking federal removal have gestured vaguely toward the Constitution’s Take Care Clause, which requires the president to see that the nation’s laws be “faithfully executed,” as a potential defense. Their theory is that they had a responsibility to ensure clean elections and so were conducting federal business when they interfered in state electoral certifications. But Judge Jones rejected this argument in a footnote when he tossed Meadows’s case back to state court.

“The Court accordingly rejects Meadows’s suggestion that the Take Care Clause provides a basis for finding executive authority over state election procedures,” he wrote in a footnote, adding that “It would be inconsistent with federalism and the separation of powers, to find that activities which are delegated to the states are also within the scope of executive power because the executive branch may advise Congress.”

That’s devastating to Meadows and Trump. Because even if the 11th Circuit rules that sloppy drafting by the prosecutors gets them into federal court, Judge Jones has already said he’s not going to allow them to defend themselves by claiming that their actions were authorized under the Constitution.

In the meantime, the prosecution has marched on, since criminal removal does not halt state procedures until the federal court actually accepts jurisdiction. This hasn’t stopped Meadows from unsuccessfully demanding that Judge Jones order DA Willis to back off, sparing him the ignominy of being arrested and having to post bond. And he’s still at it, petitioning the court to stay its remand order — although the effect will be nil, since 28 U.S. Code § 1455 explicitly allows the state action to continue.

All told, it’s very bad news for Meadows, and perhaps even worse news for Trump himself.

That’s it for today

We’ll be back with more tomorrow. If you appreciate this post and aren’t already a paid subscriber, please support our work by becoming one.

Someone needs to put a mic and camera on Lindsey (got any truth serum handy?) and ask him if ANY Senator who was the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee has EVER called a state to ask about how they match signatures, count ballots, throw out ballots, whatever his latest story is - no matter what state they are from or which state they called. His 'splainin ain't even working for Lucy.

Would Judge Jones be the presiding judge over the case should the appeals court reverse him and remove it to federal court?