"The reality is most people can only see as far as their lived experience"

On the first day of Black History Month, conversations with two young Black leaders.

Black History Month isn’t just about the past. It’s about about the leaders and thinkers who are on the front lines of the Black experience, highlighting issues of equity, systemic racism, and the possibility of a better tomorrow. To usher in the first day of Black History month, I spoke with two of them.

The first is Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, a researcher, entrepreneur, writer, and student at the Harvard Kennedy School who last year published The Black Agenda, a book featuring a collection of essays from Black experts centering their perspectives on how to address systemic problems in America. Opoku-Agyeman and I have been Twitter pals for years, and last month I had the pleasure of meeting her when she was in St. Paul to deliver an MLK Day speech to an audience that included top Democratic leaders in the state. We connected on the phone a few days later.

“I think we all lose when Black and brown voices, especially Black voices, are not platformed,” she told me. “When we talk about economic policy, what does it mean when the economists were raised the same way, or probably friends with each other and have the same background? We miss out on policies that are actually going to address the economic needs of people.”

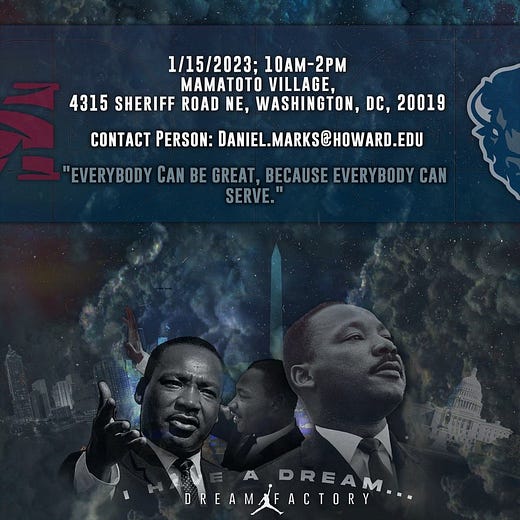

I also spoke with Jelani Williams, captain of the Howard University basketball team, which this year organized a social justice project on Black maternal health. The team’s work featured a day of service last month at Mamatoto Village in DC where players packed pregnancy and lactation kits, as well as a number of educational workshops aimed at making them informed advocates for Black moms, which in DC represent 90 percent of pregnancy-related deaths.

“I also didn’t fully realize that a lot of the deaths and a lot of the childbirth-related issues are preventable,” Williams told me. “A vast majority of them are due to medical neglect and a lack of resources. That was something that struck me as very fixable and shouldn't be happening still in 2023 at the rate that it's happening.”

Opoku-Agyeman and Williams are thoughtful advocates for their communities, and by extension for all of us. A transcript of my conversations with them, lightly edited for clarity and length, follows.

Public Notice is entirely funded by readers and made possible by paid subscribers. To support this work, please click the button below and sign up to get our coverage of politics and media directly in your inbox three times a week.

Aaron Rupar

The Black Agenda was written in 2021. A big theme of your introduction to the book is how underrepresented Black voices are in public conversations and institutions. Nearly two years later, do you think any progress has been made?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

It's bad. The New York Times during ran a series of articles over a year ago showing that there was less support for Black Lives Matter in 2021 than there was before all of the Black Lives Matter protests of the year before. People in power grew fatigued by folks fighting for justice.

We’re still very much at the place where we’re centering Black people only when it’s convenient. Like, “We need a Black person here because we don't want our brand to look bad,” or “we need a Black person here because it's Black History Month, or it's Juneteenth.” Juneteenth actually is a really good example. Juneteenth 2022 was a mess. You had articles coming out about Juneteenth flavored ice cream. You had individuals talking about watermelon salad. Those are examples of Black experts definitely not being centered, because any Black person would've told you those things were inappropriate.

So if you’re an organization or a corporation and you are making mistakes like that, then I don't think you have actually learned from all of the calls to action in 2020, and that's really concerning. There's been a little bit of a white-lash that has happened. That’s why The Black Agenda is evergreen, because there’s that push and pull between calling for justice, fighting for justice, and then there's an immediate backlash.

Aaron Rupar

Right around the time you’re putting together the book, Biden was taking office from Trump and Democrats gained full control of the federal government for the first time in a decade. How did Dems do in those two years when it comes to addressing systemic issues facing the Black community?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

First off, I think Trump was emblematic of a backlash to Black and brown folks having a bit more agency in the United States, and I think that’s why a lot of people identify with him. He represents all the things people want to say but can’t, or all the views they weren’t able to express during the Obama years.

But to answer your question about Democrats and what the heck they did between 2021 and 2023, it's interesting because when President Biden won, he appointed a lot of Black people. A lot of his cabinet was Black and brown. You can have people who are public facing who are Black and brown, but how much power do they actually have? Are they being listened to? Are they being cited? Are they being valued? And it's not clear to me based off of how much didn't get done that those perspectives were really being prioritized.

The Covid response is a really great example. A lot of Black and brown experts were talking about how Covid was having these disproportionate effects on their communities, on our communities. And I don't think anybody really listened to them until it was too late and a million people died. Now you're starting to hear more conversations around racial inequalities, but at this point the CDC has kind of botched this. It's not entirely clear what the Democratic Party has done to really heed the warnings that Black experts have provided since the start of the pandemic, and there's been a tremendous cost for everyone, but especially for Black communities.

Around elections there's always like, “Here's all the promises I'm gonna make to you guys, thanks for getting me elected.” But then it’s like, “Well, actually, there are higher priorities than your humanity or life conditions.” That's concerning. And that's a lot of the frustration the Black community has with the Democratic Party is that we come out every election and vote overwhelmingly for them, yet we don't really ever see any tangible benefits in our own communities.

Aaron Rupar

That dovetails into my next question. The Wall Street Journal did a poll last November showing Republicans making significant gains in the Black community. What explains that?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

When someone says, “Hey, if you fall, I got you,” and they keep dropping you over and over, you might be like, “Uh, maybe I need to fall somewhere else or maybe I shouldn’t fall at all.” The trust has eroded over time and I think people are looking for new places and new people to trust. And I would point out too that there are quite a few people who have conservative views within the Black community, especially those raised in the evangelical Christian tradition. But a lot of times they're deterred from being part of the Republican Party because of the racism, even if they might align on things like abortion and taxes.

The other question to ask is, who's driving that increase in Black conservative support? I'm gonna make an assumption and say it's probably not Black women. Black women overwhelmingly vote Democrat every election and have for a while. I think that goes back to the idea around “black women best,” which was coined by Janelle Jones, the first Black woman to be the chief economist of the Department of Labor. She says that the best outcome for Black women is a better outcome for everyone else. And so a lot of times when people bring up polling numbers around certain candidates or certain policies, I ask the question, “How did Black women vote?” Black women are among the most vulnerable next to Native American women and Latino women, and so oftentimes when Black women vote they’re voting for something inclusive of all groups.

So there might be an increase in Black conservative support, but who's driving that increase and why? And how does that kind of vary across race, class, and gender?

Aaron Rupar

Economic issues are in the news now more than they normally would be because of the looming debt ceiling fight. Republicans want concessions in exchange for allowing America to pay its debts, including possibly cuts to the social safety net. But when you turn on TV and see coverage of this issue, you’re not hearing a lot of Black voices. What do you think gets lost in a conversation like this when Black voices aren’t platformed?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

That's a really good question. I think we all lose when Black and brown voices, especially Black voices, are not platformed. And that's because we're not seeing the full picture of the economy. As Angela Hanks once said, economic progress for some is not economic progress for all. And I would also argue that economic crises are worse for some than others. This debt ceiling conversation, what we are seeing with inflation, what we are seeing with how unemployment shot up during the pandemic — the group that lost the most was the Black community, and I would argue more specifically Black women. At the peak of unemployment in the pandemic, Black women had a unemployment rate of 17 percent, higher than any other group.

When we talk about economic policy, what does it mean when the economists were raised the same way, or probably friends with each other and have the same background? We miss out on policies that are actually going to address the economic needs of people. The reality is most people can only see as far as their lived experience. And so the beauty of Black experts, and even more specifically Black economists, folks like Dr. Lisa D. Cook and Dr. Gbenga Aijlore, is that these individuals have both the lived experience of having some proximity to what economic crisis can do to their community and also have the expertise to back up why their lived experience is worth talking about and addressing. And so that's what we miss when we don't include Black voices in this conversation around economic policy.

Aaron Rupar

Your next book is called The Double Tax. What’s it about?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

I'm gonna be comparing the experiences of Black and white women, experiences that have been compared quite a bit in feminist and womanist work, but very rarely in the mainstream and especially in economics. It’s going to be a bit of a cost-benefit analysis to show what the difference between Black and white women teaches about inequality in America and beyond. I’m hoping to illustrate it through the lens of looking at an average woman’s life — being a teenager and mother and deciding to buy a home and move up in a career. The hope is that by kind of using the lens of a person's life, I can parallel the experiences of how racial identity shapes women's outcomes at every stage of life, and the literal costs borne by women at those stages of life.

In a lot of conversations about women empowerment, you hear a throwaway term that used to be really big back in the day — “girl boss.” Folks now use it in derogatory ways — like, “why is she a girl boss?” And you hear a lot of these conversations about women empowerment that are oftentimes led by very wealthy white women. The reality is wealthy white women can't speak for white women who are middle class, who are from poorer backgrounds, and they can't speak for any other group that is a different race or ethnicity or has different experiences.

And so the big argument in The Double Tax is this idea that there's a compounded cost of racism and sexism and it's incurred fully by Black women and partially by everyone else. At one end of the spectrum is Black women. And at the other end of the spectrum is white women and white women of a particular class. So that's what the book is gonna get at without giving too much away. It's a very ambitious project.

Aaron Rupar

Parting question — who are some of the Black experts you really think Public Notice readers should be paying attention to?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman

If folks wanna know anything about education, especially in the K12 space, I recommend Dr. Lauren Mims. I love, love her essays — she wrote maybe my favorite one in The Black Agenda. In the climate space, Abigail Thomas. She's associated with the intersectional environmentalist movement that was started by Leah Thomas, another good friend of mine. Both of them are around my age, so they are some young voices that people can check out. I would say in the health care space, Dr. Jaime Slaughter-Acey. Folks might be seeing a little bit more of her, because she's a contributor that I really wanna kind of bring some attention to this upcoming year.

In terms of economics, several people, because that’s my field of expertise, including Dr. Aijlore. He does a lot of stuff around rural America as it relates to the Black community. Dr. Jevay Grooms has done a lot of good work around mental health in Black America. The person that many people know is Dr. Sandy Darity. If you're interested in anything around reparations, that's your man. And then I would say, finally, the tech space is really big and I would argue that Black women are really at the helm of that conversation. Deborah Raji is really, really amazing. She's doing a lot of work around AI equity and regulation and how AI is affecting vulnerable communities.

I would also recommend Ashlee Wisdom, who’s the co-founder of Health in Her HUE. It's an application that's used for Black and brown women to find health providers that provide culturally competent care. Finally I would like to shout out Tinu Abayomi-Paul. She’s a disability activist and someone that people should really be following to understand how Covid is basically a mass disabling event, and how what happens to the disabled community is pretty indicative of what's gonna happen to the rest of us.

“It's about trying to lift the whole rather than highlight the few”

Aaron Rupar

How did Howard basketball as a team decide to focus on Black maternal health for a social justice project?

Jelani Williams

At the beginning of the year, coach [Kenneth Blakeney] challenged us to come up with the social justice initiative that we wanted to advocate for. And so we started thinking about some of the bigger political issues over the past year — Roe v Wade being overturned, the Voting Rights Act, and different things like that. But being at an HBCU where 80 percent of the student body is women, and the majority of us have Black mothers and Black aunts, Black cousins, and Black friends that have been a big part of our lives, we just felt like it would be the most impactful to advocate for Black women and try and shine a light on an issue that isn’t highlighted as much as it probably should be.

Aaron Rupar

What have you learned about Black maternal health during the process of doing this service project that you didn’t know coming in?

Jelani Williams

I was familiar with the blanket statement that Black women and Black babies generally are more at risk to die or have pregnancy-related issues during or after childbirth. But what was kind of staggering to me was being in DC, our nation’s capital — “Chocolate City” — which has been majority Black for a long time, that Black mothers are way more likely than others to die during or after childbirth. I grew up here, we have a Black woman mayor, but learning that was definitely staggering to me.

I also didn’t fully realize that a lot of the deaths and a lot of the childbirth-related issues are preventable. A vast majority of them are due to medical neglect and a lack of resources. That was something that struck me as very fixable and shouldn't be happening still in 2023 at the rate that it's happening.

Aaron Rupar

I know you recently transferred to Howard from Penn University, where you got coverage for your advocacy against systemic racism. What’s your perspective on those issues now that you’re back in your hometown?

Jelani Williams

I grew up here and went to DC public school before going to a public school in Prince George’s County, Maryland, which is also majority Black. I’ve been blessed by being able to play basketball and having pretty good grades, so eventually I was able to go to one of the better private high schools in the area [Sidwell Friends School]. And then going to the University of Pennsylvania and now being at one of the better HBCUs, I think the biggest thing that I try to carry with me for other men of color I grew up with is that they couldn't even sniff the opportunities that I've had.

And so I think that's the biggest thing — how do we reach other young men in my community or where I come from that haven’t had the same opportunities? I was raised by two teachers and educators, and the importance of education was stressed to me. I'm 6’5” and can dribble a basketball, and that has been able to put me in different rooms and get me a different level of education, a different understanding of what the world is. But that’s just not something that's afforded to everybody that looks like me. And so when people ask me what's the biggest issues are that affect black men, I think it's a lack of opportunity and inability to move upward. I think it's about trying to lift the whole rather than highlight the few that are able to climb the ladder.

That’s it for today

I’ll be back with more Friday.

I soooo love your writing. Thank you for these wonderful interviews with outstanding young change makers. It makes me wonder though, how is it that *we* don’t know about the field trailblazers the young lady highlighted. Why is their expertise not in mainstream conversations? We’ll you’ve shined a spotlight. TY

Thank you Aaron for bringing these

wonderful young people to our attention. President Biden needs

to meet them and make use of their

keen insights.